#Philippe-Paul de Ségur

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I wish I had something more substantial to contribute to Fouché Friday, but here’s a great description from Ségur’s memoirs.

Everybody knows this personage; his medium stature, his tow-coloured hair, lank and scanty, his active leanness, his long, mobile, pale face with the physiognomy of an excited ferret; one remembers his piercing keen glance, shifty nevertheless, his little, blood-shot eyes, his brief and jerky manner of speech which was in harmony with his restless, uneasy attitude.

Source: An aide-de-camp of Napoleon. Memoirs of General Count de Ségur, of the French academy, 1800-1812.

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just read your Duroc rant, do YOU think that maybe there was more between them? (Not asking for sources/evidence, just your piece)

(Rant in the tags on this post, for context.)

Anon, I can’t complain about people not giving any citations for their claims and then not provide sources myself. 😉

That said, the short answer is no, I don’t think so. I think they were extraordinarily close—I wrote a while back about how intimately entwined their lives were—but their relationship simply doesn’t strike me as romantic in the way that, say, Junot’s feelings towards Napoleon do. (Or, to be strictly accurate, the way Laure Junot portrays her husband’s feelings towards Napoleon in her memoirs does.)

The much longer and more rambling answer, with sources:

Obviously, there’s no way to truly know how someone who’s been dead for over two hundred years felt. Even so, Duroc is particularly hard to grasp—leaving aside that he died too suddenly to leave behind any kind of memoirs, or that his administrative correspondence is far more voluminous than his personal correspondence, his reserve during his lifetime was notorious. Caulaincourt mentions at one point in his memoirs that Napoleon claimed that Duroc “was devoted to me, but he did not love me”. (Though he allegedly made this remark in April 1814, so I’d imagine he may have been in a particularly cynical mood at the time.) Duroc’s devotion, certainly, is unquestionable—he and Napoleon were essentially inseparable from the first Italian campaign onward, and he wore an astonishing number of hats over the course of his career as he stepped into whatever role Napoleon asked of him, whether that was beginning diplomatic overtures to Russia in 1801, acting as a go-between with Marie Walewska in the winter of 1806-07, or overhauling the entire Imperial Guard in early 1813. Duroc’s role as Grand Marshal, responsible for running the imperial household, meant their lives were intertwined to a degree that was unusual even by the standards of how the Empire revolved around Napoleon (to quote Philippe-Paul de Ségur, who was Duroc’s aide de camp for a time, “They were so closely associated by nature, by habit, by everything, that we [i.e. the staff of imperial household] no longer imagined that they could live apart”). And Duroc seems to have highly valued his closeness to Napoleon, from writing to him from his diplomatic mission to Moscow in 1801 that “although I’ve been received warmly here, I am never better than when I am near you” (emphasis his) to telling Laure Junot that it would be a mark of disgrace if Napoleon gave him a marshal’s baton: “What would I do away from his side?” There’s love there, to my mind at least.

As for Napoleon, his feelings towards Duroc are more well-documented by virtue of the sheer mass of sources, though of course there’s a certain amount of after-the-fact romanticization going on due to having lost one of his closest friends in an incredibly awful way (such as his letter to Marie Louise the day after Duroc’s death, in which he wrote, “He had been my friend for 20 years. I never had a reason to complain about him; he gave me nothing but comfort.”). And there’s an element of myth-making to it as well: his claim that Duroc was the only person who “had his intimacy and possessed his entire confidence” comes in the Mémorial de Sainte-Hélène, which is firmly aimed at establishing his legacy. That said, the sheer number of people who described his death as an “irreparable loss” for Napoleon were getting at something important. They’d been friends since at least 1796; while I’ve never found a truly convincing source for the frequently-cited claim that Duroc was allowed to tutoyer him in private, I do think that it was a friendship that transcended their official roles as the Emperor and his Grand Marshal, and that Duroc was, while not unique, certainly in an increasingly small number of people who loved and saw Napoleon Bonaparte the individual as well as Napoleon the Emperor of the French. (Back to the Mémorial, Las Cases argues that Duroc was devoted to the private man rather than the monarch.) When Napoleon surrendered to the British in 1815, envisioning that he was going to live out a comfortable retirement in the English countryside, he suggested he could live under the name of Colonel Duroc: they were still inseparable, even two years after Duroc’s death.

The always-astute @thiswaycomessomethingwicked wrote something a few months ago that chimes with my interpretation also: that Napoleon was on some level attracted to men as well as women (see the infamous quote from Caulaincourt’s memoirs about how his closest friendships with men started with feelings in the loins “and another place which shall be nameless”), but the cultural taboos and baggage of late 18th/early 19th century France meant that he wasn’t fully aware of or able to understand it, let alone being in a position to act on that attraction or considering himself in a similar category to people like Cambacérès.

The quote I was complaining about in my original post frames Duroc and Napoleon’s relationship in a strikingly similar way to a couple of contemporary publications (Lewis Goldsmith’s scandalous The Secret History of the Cabinet of Bonaparte (1810), and an 1813 article in an English paper that was essentially a spotter’s guide to the French court): a remarkably handsome young man with no particular talents or family to recommend him, who nevertheless attains a high rank at the imperial court owing solely to Napoleon’s favor. I don’t think that’s an accurate description of Duroc at all, but it positions him in a particular, established mode of court favorite (the Buckingham to Napoleon’s James I, to pick another example I’ve been reading about recently), with the corresponding implications of a sexual relationship with the monarch. We can speculate as to whether these characterizations were responding to something specific, but I think it’s more likely that they were simply another angle for the English press to calumniate Napoleon (Goldsmith’s book also repeats the claim that Napoleon was sleeping with his stepdaughter Hortense, for example).

Also, to expand on my tag rant a little, that’s not the first time I’ve seen a published work suggest that Napoleon’s intense grief at Duroc’s death meant that his feelings towards him must have been romantic. (And then there’s Frank McLynn’s Napoleon bio, in which he compares Napoleon’s grief for Duroc to Achilles’s for Patroclus and Alexander’s for Hephaestion, and then immediately follows that with “but the inference of homosexuality is unjustified”—maybe he should have picked some different comparisons, then! Just saying.) I don’t think that this interpretation is necessarily a huge reach: it’s an unusually strong moment of emotion from Napoleon (and unusually public—it got a lengthy paragraph in the Moniteur). There are about as many versions of their final conversation as there are memoirs of the era, and we’ll never know exactly what they said to each other, so it’s very fertile ground for whatever interpretation you want to put on their relationship. I can never pass up the opportunity to quote Ségur’s Histoire et mémoires (published posthumously in 1873), because his depiction is spectacularly homoerotic:

But Napoleon still could not resign himself [to leaving Duroc’s deathbed]; falling again into his previous stupor, he fastened on his unfortunate friend one of those long and profound looks that, in those solemn and final moments, seemed to want to, in defiance of fate, indissolubly merge their souls; striving more than ever to tighten so many bonds on the verge of breaking, and to gather everything it was possible to wrest from inexorable death!

But equally, I simply don’t think it’s possible to make an absolute determination of whether Napoleon’s feelings towards Duroc were platonic or romantic—not that that should be a cut and dried binary, either—and certainly not based only on his reaction to Duroc’s death (people can be devastated at the deaths of their friends, too, obviously). This has been a whole lot of rambling to say, basically, that it’s complicated!

#this may have gotten away from me a bit lol#(also ellis i hope you don't mind me linking your post--i just thought you had a very good take as usual)#asks#duroc#napoleon

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The door of the monument was open, Napoléon paused at the entrance in a grave and respectful attitude. He gazed into the shadow enclosing the hero's [Frederick the Great] ashes, and stood thus for nearly ten minutes motionless, silent, as if buried in deep thought. There were five or six of us with him: Duroc, Caulaincourt, an aide-de-camp and I. We gazed at this solemn and extraordinary scene, imagining the two great men face to face, identifying ourselves with the thoughts we ascribed to our Emperor before that other genius whose glory survived the overthrow of his work, who was as great in extreme adversity as in success."

(General Ségur)

#Napoleon#Napoleon Bonaparte#frederick the great#Géraud Duroc#Duroc#Armand-Augustin-Louis Caulaincourt#Caulaincourt#Philippe Paul comte de Ségur#Ségur#Napoleonic era#history#french history#napoleonic wars

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another one enchanted and mesmerized by Bonaparte

I found myself the next day at the hour named in the gallery of Mars at St. Cloud, where Duroc presented me to Bonaparte. The much too flattering words which that great man let fall on this occasion, while overwhelming me with astonishment, had the effect of attaching me once for all to his person. "Citizen Segur," he said, in a loud voice, before a crowd of senators, tribunes, legislators and generals, "I have placed you on my private staff; your duty will be to command my bodyguard. You see the confidence which I place in you, you will respond to it; your merit and your talents will ensure you rapid promotion!"

As much delighted as surprised by such a flattering reception, in my agitation I could only answer by a few words of gratitude and devotion, which Napoleon received with one of his indescribably gracious smiles; continuing his way through the crowded assemblage of personages of more or less note, he went on to the gallery of the chapel in which he heard mass.

Intoxicated with joy and gratified pride beyond the bounds of expectation, and feeling as if I trod on air, I walked up and down these brilliant chambers as if taking possession of them, turning back and again stopping on the spot which even at this lapse of time I can still see before me, the spot where I had just listened to such expressions of esteem and regard, meditating upon them, and repeating them over a hundred times. It seemed to me as if they associated me, as if they identified me, with the renown of the Conqueror of Italy, of Egypt, and of France! I do not know what that autumn day was really like, but it has remained in my memory as the most beautiful, the most glorious day that ever shone upon me in my life.

When I returned to Paris to my father's humble abode, it was only with blushes and under my breath, that in telling my story I could repeat these words of praise which must have appeared almost beyond belief.

An Aide-de-Camp of Napoleon by Comte de Ségur

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Comtesse Jean-Henri-Louis Greffulhe, née Marie-Françoise-Célestine de Vintimille du Luc, later Comtesse Philippe-Paul de Ségur in a landscape by Horace Vernet , 1825

92 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello dear,

I have a question that I hope isn’t too off topic or has already been asked.

I am currently reading through Adrienne de Lafayette’s bio by André Maurois and he keeps referencing the Marquis’ friend Ségur. I recall this name from other Lafayette biographies I have read but there I encountered the same problem. Does he have a title or a first name? It appears his father was a well respected general? But I can’t seem to piece together who that family is or what their standing was. I would love to know more about him, maybe dig into some correspondence as that is my one true vice. 😆 I just thought I would ask the Oracle since I’m stumped. 🤓😁

Well my dear @aconflagrationofmyown, I think I can help you with that. :-)

Yes, this mysterious Ségur has a name and a title. The “Ségur in question” was Louis Phlippe, comte de Ségur, born on December 10, 1753 in Paris and died on August 27, 1830 in Paris. He published his Memoirs and they are really worthwhile to read - interesting stories about a young La Fayette, insights into the inner circles of the French court at the time and of course into Ségur’s personal life. Here is his description of his relationship with La Fayette:

The three Frenchmen, distinguished by their rank at court, who first offered their military services to the Americans , were the Marquis de La Fayette, the Viscount de Noailles, and myself. We had long been intimate friends, and our connexion, which was strengthened by a great conformity of opinions, was soon after confirmed by the ties of blood.: La Fayette and the Viscount de Noailles had married two daughters of the Duke de Noailles, then bearing the title of Duke d'Ayen; their mother, the Dutchess d’Ayen, was the daughter, by his first marriage, of M. d'Aguesseau, Counsellor of State; and son of the Chancellor of that name M. d'Agur esseau had, by a second wife, twenty years after, several children, one of whom was M. d'Aguesseau, now a peer of France, a daughter, married to M. de Saron, first President of the Parliament of Paris, and another daughter, to whom I was united in the spring of 1777; so that, by this alliance, I became the uncle of my two friends.

Comte de Ségur, Memoirs and Recollections of the Count Segur, Ambassador from France to the Courts of Russia and Prussia, &c. &c., Wells and Lilly, Boston, 1825, p. 84.

Ségur’s descriptions of family relations is as confusing as it could possibly be and therefor once more in simple terms. La Fayette’s wife Adrienne had an aunt, her mother’s younger sister Antoinette-Elizabeth-Marie d’Aguesseau. This sister married Louis Philippe, comte de Ségur in 1777 in Paris and the couple had four children, three sons and one daughter. Ségur therefor was La Fayette’s uncle by marriage. Here is an example of how La Fayette described Ségur and their relationship. He wrote to George Washington on April 12, 1782:

This letter, My Dear General, Is Intrusted to Count de Segur, the Eldest Son of the Marquis de Segur Minister of State and of the War Departement Which in France Has a Great Importance—Count de Segur Was Soon Going to Have a Regiment, But He Prefers Serving in America, and Under Your orders—He is one of the Most Amiable, Sensible, and Good Natured Men I Ever Saw—He is My Very Intimate friend—I Recommend Him to You, My dear General, and through You to Every Body in America Particularly in the Army.

“To George Washington from Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, 12 April 1782,” Founders Online, National Archives, [This is an Early Access document from The Papers of George Washington. It is not an authoritative final version.] (05/20/2022)

You said you have already done some digging on your own and I assume you came across Ségur’s Memoirs. I include some links just in case and for everybody else who might be interested. Ségur’s memoirs are normally split into three volumes.

Internet Archive, French original: Volume One - Volume Two - Volume Three

Internet Archive, English Translation: Volume One (they do not have any more volumes in English)

Google Books, English Translation: Volume One - Volume Two - Volume Three

Since Ségur also worked as a diplomat and historian, he authored quite a number of works. Here is a little overview of all of his freely accessible books at the Internet Archive and via Google Books.

His second-oldest son, Phillipe-Paul also wrote his memoirs: An aide-de-camp of Napoleon. Memoirs of General Count de Ségur, of the French academy, 1800-1812.

Ségur hailed from a very well situated family. His father was Philippe Henri, Marquis de Ségur, decorated general and later Secretary of State for War during the American Revolution. He was the grand-son of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, regent of the Kingdome of France, by Orléans’ illegitimate daughter Philippe Angélique de Froissy. Ségur also had a younger brother, Joseph Alexandre Pierre, vicomte de Ségur. It is rumoured that Joseph Alexandre Pierre was not the son of Phillippe Henri but had actually been fathered by his “fathers” friend, Pierre Victor, baron de Besenval de Brünstatt. To my knowledge that had never been officially proven though.

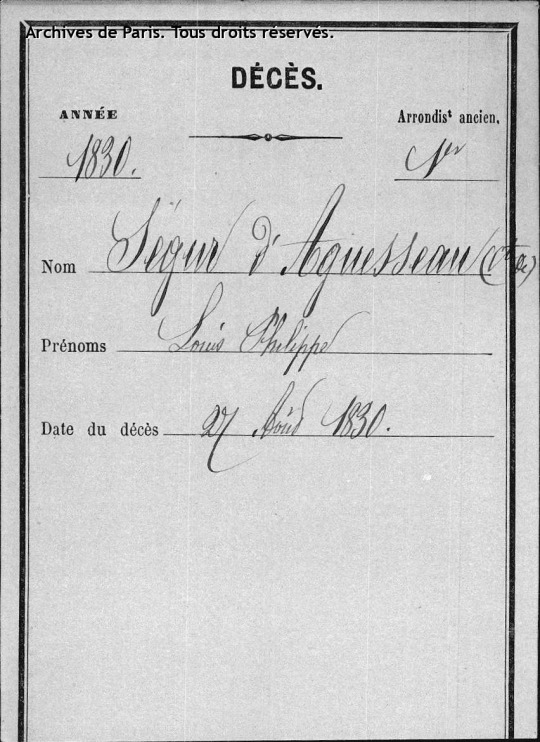

The État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859) should technically have Ségur’s Acte de Décès but I could not find it at first glance. I did find however the corresponding Fichier in the État civil reconstitué and maybe that is of interest for you as well. It is quite interesting to observe that Ségur’s last name is given as a combination of his and his wife’s name.

Paris Archives, Fichiers de l'état civil reconstitué, Cote V3E/D 1356, p. 21. (05/20/2022)

You also mentioned that you were interested in correspondences - in fact, you said that they are your one true vice and I can absolutely understand that. Under the cut (as not to bother everybody who is just casually scrolling) I include the one fully transcribed letter by Ségur that I have. There are also a couple of letters where I only have the dates and short summaries - just let me know if you are interested in them as well.

I hope you have/had a beautiful day!

The comte de Ségur to the Marquis de La Fayette

Rochefort, July 7, 1782

I received, my dear Lafayette, your friendly letter, and I was extremely touched. I love you madly and I cannot console myself that I am not traveling with you. You are going to play a very honorable role, and one that is very difficult to play. You will have to reconcile the French and American characters, deal tactfully with opposing interests, and fill the measure of your glory to overflowing by adding the olive branch to the laurel leaves. And you will even have to act against your own inclination by helping to put a definite end to the horrible scourge to which you owe your fame. I am very sorry not to be able to talk with you freely at the moment I most desire it. But letters are not safe enough, and I haven't anything to tell you but things I would not want to be read. I foresee that you are going to be more revolted than ever at English arrogance, stupid Spanish vanity, French inconsistency, and despotic ignorance. You will see that the cabinet tries one's patience as much as a battlefield, and that as many stupid things are done in a negotiation as in a campaign. You will see especially how essentials are sacrificed to form, and you will say more than once, “If chance had not made me one of the principal actors, I should certainly not stay in the theater.” But the more obstacles you encounter, the more merit you will gain. How could you not succeed in all you desire, for you have genius and good fortune. To have that is to have half again as much as it takes to be a great man. Farewell, my friend. I expect to leave the day after tomorrow, consoling myself rather philosophically for going two thousand leagues for nothing, but not consoling myself for not finding you in a place that I find full of your name and your deeds. I shall carry out all your commissions, and I shall point out the patriotic sacrifice you are making in temporarily exchanging your sword for a pen. I request that you love my wife, hug my children, take my place with my father, and join us as soon as you can to sound the charge or beat the farewell retreat.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 5, January 4, 1782‑December 29, 1785, Cornell University Press, 1981, p. 51.

#ask me anything#aconflagrationofmyown#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#american history#american revolution#french revolution#history#letter#george washington#comte de ségur#marquis de ségur#vicomte de ségur#1753#1777#1730#1782

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

stephmilanez

Duvido que te contaram isso na escola! Por acaso, você sabia que a Vodka ajudou a Rússia a vencer os duas importantes guerras? 😈 A da vitória Soviética na 2° Guerra mundial teve ajudinha da vodka. Em 1943, o marechal russo Georgui Jukov informou a Stalin que as tropas estavam utilizando a vodka para impedir que a água dos radiadores congelasse, ja que não tinha descongelante, a vodka foi a salvação. 😏

130 anos antes da vitória Russa na segunda guerra mundial, a vodka também teve um papel importante contra outro grande inimigo: Napoleão Bonaparte. O general francês e historiador Philippe-Paul de Ségur, que participou do enfrentamento com a Rússia em 1812, descreveu em seu livro que os soldados franceses estavam adoecendo e morrendo por beber vodka russa. “Nossos jovens soldados, enfraquecidos pela fome e o cansaço, achavam que esta bebida restauraria sua energia, mas o calor (da bebida) fez com que eles gastassem o resto de energia como em uma explosão e depois caíssem esgotados”. Assim é vida, quem não aguenta bebe leite.

Vodka Russa não é apenas uma bebida, faz parte da vida e da história das pessoas. Ontem o mundo comemorou 75 anos do Fim da 2° Guerra Mundial, o término da mais terrível e devastadora guerra travada pela humanidade, que matou milhares de pessoas. Como falei nos stories de ontem, guerra não é uma luta do bem contra o mal, é feita de pessoas comuns, heróis, soldados, jovens, covardes e todo tipo de gente em todos os lados. Então vamos usar essa data para celebrar a paz, que todos povos do mundo possam se orgulhar do seu país e dos seus heróis. Recordar o sofrimento dos nossos familiáres que enfrentaram o período sombrio que é uma guerra e agradecer a bravura deles que nos fez estar aqui hoje. Um brinde à Paz!

@kalashnikov.vodka

Nasdróvia!

1 note

·

View note

Photo

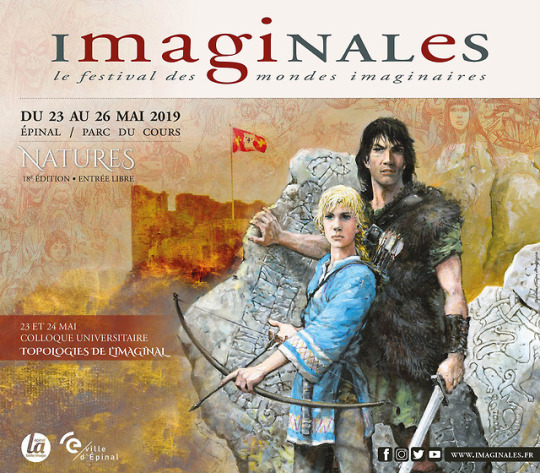

Imaginales: le festival des mondes imaginaires, 18ème édition. 23-26 May 2019, Ville d’Épinal, France. Poster art by Grzegorz Rosiński and Piotr Rosiński, info: imaginales.fr.

From Thursday 23rd to Sunday 26th May, 2019, more than 300 authors and illustrators from all over the world will come to Epinal, in France, for the 18th edition of Imaginales: le festival des mondes imaginaires, one of the first international exposition of Imaginative literature. Artists, novelists and experts in the Fantasy, SF and Fantastic genres will share their stories with a varied and enthusiastic audience. Founded in 2002, the festival is free and open to the public, welcoming more than 40,000 visitors from all over France.

Guest list:

Comics and illustration – Julien DELVAL, Renaud DENAUW, Emmanuel DESPUJOL, Steven DUDA, Gilles FRANCESCANO, Laurent GAPAILLARD, Armel GAULME, Didier GRAFFET, Loïc JOUANNIGOT, Milan JOVANOVIC, Frédéric MARNIQUET, Gilles MEZZOMO, Noë MONIN, Thimothée MONTAIGNE, Frédéric PILLOT, Michel RODRIGUE, Olivier ROMAC, Grzegorz ROSIŃSKI, Piotr ROSIŃSKI, Thierry SÉGUR, Olivier SOUILLÉ, Philippe ZYTKA.

International authors – Alex BELL, Sigridour Hagalin BJÖRNSDOTTIR, Peter BRETT, Anders FAGER, Mark HENWICK, Vic JAMES, S.T. JOSHI, Hildur KNÚTSDÓTTIR, Graham MASTERTON, Sam J. MILLER, Christopher PRIEST, Sofia SAMATAR, Johanna SINISALO.

French authors – Christophe ABAS, Sandrine ALEXIE, Nicolas ALLARD, Mel ANDORYSS, Jean-Pierre ANDREVON, Jacques BARBÉRI, Isabelle BAUTHIAN, Robert BELMAS, Paul BEORN, Karim BERROUKA, Georges BERTIN, Chloé BERTRAND, Pierre BORDAGE, Béatrice BOTTET, Nicolas BOUCHARD, Clément BOUHÉLIER, Charlotte BOUSQUET, Fabienne BRUGERE, David BRY, Sabrina CALVO, Nicolas CARTELET, Fabien CERUTTI, Fabien CLAVEL, Guy COSTES, Alain DAMASIO, Grégory DA ROSA, Nathalie DAU, Lionel DAVOUST, Nicolas DEBANDT, Romain DELPLANCQ, Jérôme DIDELOT, Julie de LESTRANGE, Marie-Charlotte DELMAS, Jean-Laurent DEL SOCORRO, Patrick K DEWDNEY, Romain D'HUISSIER, Victor DIXEN, Sara DOKE, Catherine DUFOUR, Jean-Claude DUNYACH, Silène EDGAR, Manon FARGETTON, Estelle FAYE, Franck FERRIC, Fabien FERNANDEZ, Élise FISCHER, Alexis FLAMAND, Célia FLAUX, Victor FLEURY, Jean-Pierre FONTANA, Isabelle FOURNIÉ, Thomas GEHA, Alison GERMAIN, Eric GIACOMETTI, Régis GODDYN, Marie-José GONAND, Alain GROUSSET, Lauric GUILLAUD, Colin HEINE, Johan HELIOT, Loïc HENRY, Ariel HOLZL, Raymond ISS, Jean-Philippe JAWORSKI, Gabriel KATZ, Florian KIEFFER, Katia LANERO ZAMORA, Gilles LAPORTE, Camille LEBOULANGER, Fabienne LELOUP, Christian LÉOURIER, Jérôme LEROY, Érik L'HOMME, Jean-Marc LIGNY, Méropée MALO, Eric MARCHAL, Jean-Luc MARCASTEL, Johanna MARINES, Jean MARIGNY, Danielle MARTINIGOL, Xavier MAUMÉJEAN, Patrick McSPARE, Hélène P. MÉRELLE, Sylvie MILLER, Vincent MONDIOT, Pierre PEVEL, Betty PICCIOLI, Stefan PLATTEAU, Jean PRUVOST, Jacques RAVENNE, Michael ROCH, Carina ROZENFELD, Éric SANVOISIN, Stéphane SERVANT, Floriane SOULAS, Charles SUZANNE, Ketty STEWARD, Rachel TANNER, Arthur TÉNOR, Philippe TESSIER, Nicolas TEXIER, Christophe THILL, Jean-François THOMAS, Jean-Christophe TIXIER, Adrien TOMAS, Jean-Michel TRUONG, Estelle VAGNER, Laurence VANIN, Cindy VAN WILDER, Claude VAUTRIN, Flore VESCO, Frédéric VINCENT, Frédérique VOLOT, Philippe WARD, Aurélie WELLENSTEIN, Georges ZARAGOZA.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Deliberately courting death"

Ségur, in his memoir of the Russian campaign, depicts Murat as being possibly suicidal at Smolensk in August 1812.

From then on Napoleon appeared to look on Smolensk as nothing more than a halting place, to be captured by storm, and at once. But Murat, prudent when he was not excited by the presence of the enemy, opposed this decision. It was true that he and his cavalry would not be involved in this operation, yet so violent an effort seemed useless to him, since the Russians were withdrawing on their own initiative. When it was proposed that we should pursue them he was heard to exclaim, "Since they don't want a battle, we've chased them far enough. It's high time we stopped!"

The Emperor retorted, but no further record of this conversation has been preserved. However, some words the King let fall at a later date give an idea of the subject of their disagreement. "I threw myself on my knees before my brother-in-law and implored him to stop. But he couldn't see anything but Moscow. Honor, glory, rest--everything was there for him. This Moscow was going to be our ruin!" One thing is certain: when Murat parted from Napoleon his features were marked by real suffering, his movements were jerky as if he were shaken by deep, repressed emotion, and the word "Moscow" fell from his lips several times.

Not far from there, on the left bank of the Dnieper, we had set up a powerful battery on the spot from which Belliard had first noticed the enemy's retreat. But the Russians opposed us with two even more formidable batteries, and our cannon and ammunition wagons were being blown up one after another. The King drove his horse straight into this inferno, dismounted, and stood motionless. Belliard warned him that he was going to get himself killed to no purpose and without glory, but Murat's only reply was to walk closer to the danger. Those around him could no longer doubt that he had lost hope in the outcome of the war, that he foresaw a disastrous future for himself, and was deliberately courting death as the only means of escape. Nevertheless Belliard persisted, pointed out that his rashness would only result in the loss of all their lives. "Then go away, all of you!" cried Murat, "and leave me alone here!" But they refused to leave. Then the King, swinging around in anger, tore himself away from the place of slaughter, like a man saved against his will.

--Count Philippe-Paul de Ségur, Napoleon's Russian Campaign (English translation by J. David Townsend)

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

I once read that Napoleon did not allow anyone to know him intimately. Even for those who were around him all the time.

Do you think this applied to Duroc? Why or why not?

That's an interesting question--I suppose it depends on how you want to define 'intimately'!

Certainly the nature of Duroc's job meant that he spent a great deal of time with Napoleon, and was heavily involved in managing his day-to-day life. I've always thought that Philip Mansel's description (in The Court of France 1789-1830 (1988)) is a good succinct summary: in his view, Duroc "organized Napoleon's life, and was one of the most important people in it". Of course there were a huge number of people involved in keeping the imperial household--and the Empire itself--running, many of whom, as you say, were around him all the time. However, Duroc's involvement in Napoleon's life went well beyond his official roles, most notably with his oft-remarked ability to influence Napoleon's opinions and decisions (Louis-François-Joseph de Bausset, who as one of the Prefects of the Palace worked closely with both Duroc and Napoleon, described Duroc as Napoleon's conscience). And he was tasked with activities that were definitely not part of his job description and touched on a more private side of Napoleon's life: carrying notes to Marie Walewska, for example, or retrieving letters Napoleon wrote to another mistress. Bausset claimed that "Napoleon had no secrets from [Duroc], while he had them from everyone else, even the prince of Neufchâtel [Berthier]".

Philippe-Paul de Ségur, who worked for Duroc in the Maison impériale, described him in his memoirs (Histoire et mémoires, 1873) as:

"Napoleon's most intimate confidant, his most devoted servant, his firmest friend; they were so closely associated by nature, by habit, by everything, that we no longer imagined that they could live apart: it appeared to us that fate couldn't tear one away without mutilating the other!"

And while Ségur's description of how inseparable they were is particularly vivid--and serving a literary purpose, as it leads right into his account of Duroc's death--he's far from the only person to remark on their closeness. So by dint of both the nature of the Grand Marshal's job and the trust that Napoleon had in him specifically, he did have an unusually intimate position in Napoleon's life.

This also gets into the question of where Napoleon Bonaparte, the person, stops, and The Emperor Napoleon begins. Emmanuel de Las Cases claimed that "it was to the private man above all that [Duroc] was devoted, far more than the monarch". (And speaking of Las Cases, he also wrote that "the Emperor told me that Duroc alone had his intimacy and possessed his entire confidence"--though as with everything Napoleon said on Saint Helena, when his myth-making was in full swing, that should be taken with a grain of salt.) Writing to Marie Louise after Duroc's death, Napoleon remarked that "he had been my friend for twenty years"--their relationship had begun well before Napoleon seized power. So there's that level of intimacy as well: recognizing and loving the man behind the complicated performance and power of the Emperor.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Borodino

Walton Ford, Borodino (2009)

~~

from History of the expedition to Russia, undertaken by the Emperor Napoleon, in the year 1812, by Count Philippe-Paul de Ségur (1824, original here). Ségur was a general and aide-de-camp to Napoleon during the Russian Campaign, and here describes the field after the Battle of Borodino, 7th September, 1812:

"The emperor could not value his victory otherwise than by the dead. The ground was strewed to such a degree with Frenchmen, extended prostrate on the redoubts, that they appeared to belong more to them than to those who remained standing. There seemed to be more victors killed there, than there were still living. Amidst the crowd of corpses which we were obliged to march over in following Napoleon, the foot of a horse encountered a wounded man, and extorted from him a last sign of life or of suffering. The emperor, hitherto equally silent with his victory, and whose heart felt oppressed by the sight of so many victims, gave an exclamation; he felt relieved by uttering cries of indignation, and lavishing the attentions of humanity on this unfortunate creature. To pacify him, somebody remarked that it was only a Russian, but he retorted warmly, "that after victory there are no enemies, but only men!" He then dispersed the officers of his suite, in order to succour the wounded, who were heard groaning in every direction.

Great numbers were found at the bottom of the ravines, into which the greater part of our men had been precipitated, and where many had dragged themselves, in order to be better protected from the enemy, and the violence of the weather. Some, groaningly, pronounced the name of their country or their mother; these were the youngest: the elder ones waited the approach of death, some with a tranquil, and others with a sardonic air, without deigning to implore for mercy or to complain; others besought us to kill them outright: these unfortunate men were quickly passed by, having neither the useless pity to assist them, nor the cruel pity to put an end to their sufferings. One of these, the most mutilated (one arm and his trunk being all that remained to him), appeared so animated, so full of hope, and even of gaiety, that an attempt was made to save him. In bearing him along, it was remarked that he complained of suffering in the limbs which he no longer possessed; this is a common case with mutilated persons, and seems to afford additional evidence that the soul remains entire, and that feeling belongs to it alone, and not to the body, which can no more feel than it can think.

A Russian veteran of Borodino, Akim Voitynyuk (Аким Войтынюк), seated last on the left, pictured in 1912 with other non-combatant witnesses of the battle. Akim is said to be 123 years old in this photo. The Russians were seen dragging themselves along to places where dead bodies were heaped together, and offered them a horrible retreat. It has been affirmed by several persons, that one of these poor fellows lived several days in the carcase of a horse, which had been gutted by a howitzer, and the inside of which he gnawed. Some were seen straightening their broken leg by tying a branch of a tree tightly against it, then supporting themselves with another branch, and walking in this manner to the next village. Not one of them uttered a groan. Perhaps, when far from their own homes, they looked less for compassion. But certainly they appeared to support pain with greater fortitude than the French; not that they suffered more courageously, but that they suffered less; for they have less feeling in body and mind, which arises from their being less civilized, and from their organs being hardened by the climate. During this melancholy review, the emperor in vain sought to console himself with a cheering illusion, by having a second enumeration made of the few prisoners who remained, and collecting together some dismounted cannon; from seven to eight hundred prisoners, and twenty broken cannon, were all the trophies of this imperfect victory."

~~

George Cruikshank, A Russian Boor returning from his Field Sports (1813)

#Cruikshank#George Cruikshank#Philippe-Paul de Ségur#Ségur#battle of borodino#borodino#cosack#cossack#dog#magpie#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#napoleonic#napoleonic wars#rook#rooks#russia#russian campaign#segur#soldier#walton ford#war#wolf

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ségur's description of Russian General Miloradovich (@tairin, you might like this--and maybe you can tell us how accurate Ségur is about him?)

Miloradovich, known to us as the "Russian Murat," commanded these troops. According to his fellow countrymen, he was a fearless warrior, astute, as impetuous as our own soldier-king, as impressively tall as he, and, like him, a favorite of Fortune. He had never been known to receive a wound, though crowds of soldiers and officers had fallen around him and several horses had been killed under him. He scorned the principles of war, even showing great dexterity in not following the rules of this art, and claiming that he preferred to surprise the enemy by unexpected sallies. He never prepared a movement in advance, counting on the place and circumstances to advise him, and acting on sudden inspiration. But he was a leader on the battlefield only, without administrative abilities of any kind, either personal or public, a notorious spendthrift, but--by contrast--honest and generous to a fault.

--Count Philippe-Paul de Ségur, Napoleon's Russian Campaign (English translation by J. David Townsend)

25 notes

·

View notes